“Couple of home visits, then we can pop home for lunch.” The general practitioner tutoring me gathered up his black bag and stethoscope, and off we set, driving to see a patient who lived in a high-rise block of flats and was unable to travel.

On the way back, as promised, we called in at the doctor’s home to meet his wife. We spent half an hour in the garden eating bread, cheese and fruit, playing with their baby and chatting about careers in general practice before heading back for the afternoon-into-evening surgery.

Back then, in 1992, I found the idea of being a GP very appealing. I was not alone; a partnership vacancy in the Aberdeen practice where I did my placement had attracted dozens of candidates.

The doctors in the centre were fun — enthusiastic, funny, knowledgeable — and could tell me about the patients before they arrived, because they knew them and their families. They understood the social and economic problems — and resources — in the community. It was solid work, sustainably paced.

I didn’t become a partner right away. I qualified as a GP when my children were small, and worked for a few years filling in as a regular locum and then working as a “retainer” — a scheme designed to keep doctors who had caring commitments in employment until able to do more. It worked — I’ve now been a GP partner in urban Glasgow for almost 20 years, serving a diverse patch covering wealthy and much poorer areas.

We still do the same work that I witnessed as a student, dealing with patients of all ages in “cradle to grave” care — acute problems such as chest infections or sciatica, long-term conditions such as diabetes or mental illnesses, and preventive care such as blood-pressure control. The difference is that the job today is essentially un-doable.

Satisfaction with GP services is now down to 35 per cent, the lowest level since the King’s Fund think-tank started its survey in 1983. NHS England estimates that there were 307.5mn GP appointments in general practice in the 12 months ending April 2019 — and 344.8mn, including Covid vaccinations, in the 12 months ending April 2023, a 12 per cent increase. But at the same time there has been a fall in fully qualified “full-time equivalent” GPs — a loss of 1.7 per cent in the year ending December 2022 — to deliver services.

A survey in Pulse magazine last year reported that most GP surgeries have one or two vacancies for permanent GP staff. Over 40 per cent of GPs who have left practice have done so because of burnout. The British Medical Journal found that 61 per cent of GPs aged above 50 intend to quit in the next five years. In short, we have too much work, too few staff, and the system — for patients, and doctors — is broken.

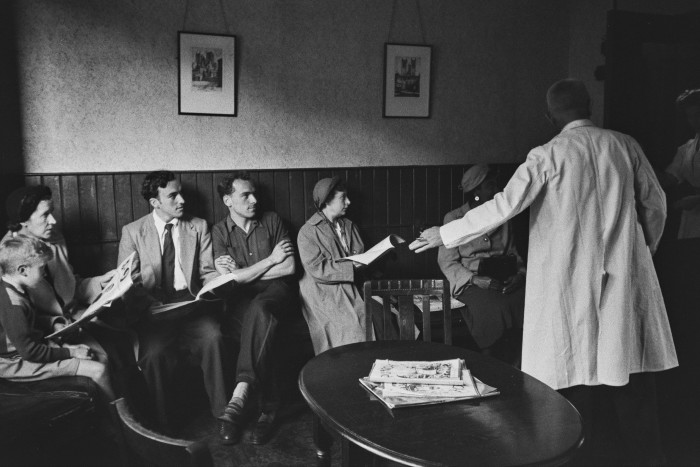

How do we improve it? It’s complicated. When the NHS was formed 75 years ago this month, GPs were not fully “brought in” — though people no longer had to pay to see them, they remained independent contractors. There was no great primary care infrastructure, with GPs often working in adapted shops or annexes built on to their own homes. It was a male-dominated profession and wives were expected to work unpaid, taking phone calls from patients at night and on weekends. People who wanted an appointment usually just turned up and waited.

The system was overwhelmed from the start — it was estimated that GPs were seeing up to 50 patients a day, as well as making at least a dozen house calls. In 1950, an excoriating report described general practice as “very unsatisfactory and at worst a positive source of public danger”. As a consequence, pay and conditions were improved, though the move of GPs from an assortment of private buildings into NHS-owned health centres envisaged by the 1948 Act didn’t happen owing to costs.

Then came a long series of political experiments. Fundholding was established under the Conservative government in 1991. It allowed GPs to hold budgets and to commission services for their patients. Under Tony Blair’s Labour government, general practitioners were given a pay rise in exchange for Quality and Outcomes Framework compliance — essentially, payment by results.

The aftermath of the pandemic, and the shift of much hospital care into the community, has contributed to the sense of crisis. Lord Ara Darzi, the academic surgeon and former Labour junior health minister, and Wes Streeting, Labour’s current health spokesman, have both argued recently for making GPs salaried rather than contractors to the NHS.

Meanwhile, other countries have quietly produced effective primary care systems and content GPs. (I felt embarrassed a couple of years ago to describe my working arrangements to Danish colleagues, who were bemused by my descriptions of wonky IT systems, the demand for appointments and the attitude of some parts of the UK press towards our work.)

As a partner, I am in effect part of a small business — a corner shop, if you will, where a few GPs employ a practice and office manager, clerical staff and practice nurses. We are tightly contracted to the NHS — private work is minimal and limited to small things, for example life insurance reports, which the NHS doesn’t pay for. Our pensions are in the NHS scheme and the rent on the premises is paid for by the local health board. What would change if I were salaried, and paid directly by the NHS?

Workload and risk, for a start. The British Medical Association and the European Union of General Practitioners both recommend that 25 “routine” doctor-patient contacts per day is more “safe”, and anything above that increasingly risky, as concentration slips and time pressures build. They may be right — though not all consultations are equal in terms of complexity — but it makes me laugh. This is an unexceptional number of contacts well before lunchtime home visits and afternoon surgery. We are unsafe by rote.

As a partner, the buck stops with me. I am “profit-sharing”, which means putting funds into the running of the practice, with the potential for gain as well as risk. Profit in small general practices is usually not huge — ask Babylon, the digital-first GP service of choice for former UK health secretary Matt Hancock, which tried to disrupt UK general practice but has failed to make a profit. The worst-case scenario for partners is known as “last man standing”, when others leave or retire and one partner is left, risking personal bankruptcy. This won’t happen to a salaried doctor, who can be employed either by profit-sharing partners or directly by the local NHS.

At the moment, there is reason to suppose that the partnership model is a fairly good deal for the taxpayer. NHS England defines full-time working for a GP as 37.5 hours a week. This is utterly unrealistic — my half-time job takes just a little less than those full-time hours. We come in early, leave late and log in from home because of the massive inbox full of test results, hospital discharge letters, prescription queries and hospital correspondence — because all of this unseen work is our responsibility.

Sure, you can make us salaried. But it may cost more than the country can afford, because all the extra, unsung, silent work being done will suddenly have to be accounted for.

Salaried GPs often work for larger “chains” of practices that operate in an amalgamation — a “supermarket” model. They usually — rightly — have clearer terms of working, with a set amount of appointments, restrictions on paperwork and no responsibility to manage the practice. Many such large practices — often on multiple sites, spread across a geographical area — are owned by a few profit-sharing partners, who employ many salaried doctors.

Some doctors may like this, particularly if they have caring commitments outside of work and need defined hours. Large chains may also be more robust — a doctor off sick is easier to manage in larger practices than in smaller ones — but they suffer the same problems with recruitment and staffing. So, commonly, large chains employ many other professionals to fill the gaps — paramedics, extended practice nurses, psychiatric nurses, pharmacists and physiotherapists.

This can be helpful. Lots of things in primary care can be dealt with effectively by staff other than GPs — practice and district nurses are integral and highly skilled — and pharmacists can free up GP time. But there are also reasons to be concerned. We know that seeing the same doctor over time is associated with lower death rates and lower secondary care costs. Continuity of care is declining, victim of the political emphasis on fast access to any doctor, not your doctor. Multiple health conditions are usual: by the age of 65, half of the UK population has two or more chronic conditions — but if you are seeing different staff members about your sore shoulder, blood pressure, dizzy spells, chronic bronchitis and depression, the risk is that care becomes fragmented and disjointed.

Clinical guidelines usually deal with one condition and don’t generally take account of the reality of such “multimorbidity”. For example, a medication to make a blood pressure “perfect” could also cause dizziness and falls. What is needed is the skill to judge and discuss how helpful guidelines are in a person’s unique situation, or not; when a drug might be useful, or create more problems than it solves.

This has led to GPs being described as the “heat sink” of the NHS — absorbing the risk that clinical uncertainty presents, and preventing the rest of the system from being overwhelmed. Because so many people are seen in general practice, tiny changes in referral rates can have profound consequences for the rest of the system. It is far easier for me to decide that someone with, say, dementia and a chest infection is safe to stay at home if I know what the person is like usually, what support they have, and can organise their follow-up care. Such rational risk-taking is far harder when we are strangers to each other.

Relationships are the currency of primary care — yet communicating with other parts of the NHS is increasingly restrictive and stressful. Older patients may have, somewhere, copies of their notes from the early days of the NHS, when GPs could refer them to hospital with a copperplate letter asking: “Please see and advise.” Now, it is an adventure in bureaucracy. I used to write letters to my hospital colleagues, explaining the need for help. Now, instead, I have a tick-box form. The three or four minutes each of these takes may not sound much, but it is significant when I have only 10-15 minutes per patient, and a slow, glitchy computer.

For politicians with quick-fix solutions, what happened to out-of-hours services when they were removed from the GP contract in 2004 is a salutary tale. Before then, many practices had evolved into local “co-operatives” in which GP partners each contributed time to cover a larger, shared area in the evenings or at weekends. GP funding is notoriously complicated, and when the government gave GPs the chance to hand back responsibility for evening and weekend cover — giving up the estimated £6,000 a year they earned for this — the vast majority of them took the offer. A couple of years later, the National Audit Office found that the actual cost of running the service was more than double that.

There are arguments for and against salaried models and “superpractices”. A system where a few partner doctors, owning chains of practices, earn vastly more than the salaried doctors they employ — and who are doing the majority of stressful, risky clinical work — makes me question the value for the taxpayer. Meanwhile, NHS doctors of all types are calling for “pay restoration” and either striking or balloting on it. Key to understanding the discontent in primary care is that earning part-time pay takes, often, near full-time hours.

This is why the argument over salaried versus partnership risks being a distraction. Instead, the focus needs to be bigger — first, on overall funding for the NHS (the UK is below the European average for numbers of beds and doctors per person and for spending), and second, on training more staff and retaining those who are already in the system. Both salaried and partnership jobs could be brilliant — and appalling. The micromanagement of clinical work, via the Quality and Outcomes Framework, has meant points, and ultimately money, for clinical decisions. It has always felt appallingly grubby, and inherently conflicted.

We have also been used as vote fodder — for example, via promises for rapid access to appointments. Certainly, some things do need quick attention. But many things can wait a day or two, and it can sometimes be better to see the doctor who knows you. As the saying goes: rapid access, continuity or quality — pick two.

Some politicians have enjoyed berating GPs for their alleged lacklustre work ethic or lack of face-to-face appointments. This sort of stuff is generally pathetic, but still saps morale. (The problem is that people can believe it. A colleague, while making a home visit during the pandemic, was asked when GPs were going to start working again. There have also been incidents of violence and graffiti in health centres.)

So much could be done to retain doctors: reduce appraisal requirements, cut down paperwork and administration, invest in decent joined-up IT and find more efficient ways to regulate services and pay us. More fundamentally, we need to ask what we can stop doing — and whether NHS management is creating supply-induced demand. For example, a ridiculous campaign a few years ago by NHS England extolled the virtues of using the NHS app or visiting a pharmacist over the winter, saying, “A minor illness can get worse quickly.” But in fact most minor illnesses go away by themselves, over-the-counter interventions are remarkably unimpressive, and all that this sort of promotion does is foster an unrealistic expectation that viral coughs lasting more than a few days need treatment (they can easily last two to three weeks).

We need slower, more considered prescribing, reducing low-value tests, tablets and treatments — not subjecting people to an industrial healthcare model. We should be advocating for professionalism, holding doctors to account but starting with the presumption that the vast majority are trying to do their best with the resources they have. We should use evidence, not hot takes from focus groups, to guide us. That requires time and trust, not just between GPs and patients but also between GPs and politicians.

Are we brave enough? At the moment, general practice in the UK is going the way of dentistry, sliding into a normality where patients who would never before have dreamt of going private are doing so.

But general practice is also amazing. We are nimble: we changed our operating processes virtually overnight in the pandemic, and were integral in the Covid vaccination rollout. We teach, train and research. We look after you, your baby, your parents and your grandparents, using the knowledge that comes from understanding people, families and communities over decades. We will spot problems before they happen, listen to you and often make diagnoses without the need for tests; recognise and treat mental and physical illness, help you navigate complex health services, advocate for you when you can’t do so yourself, visit you at home when you are dying, and support the family you leave behind.

At least, general practice could be amazing. The choice to break it has been political, not professional. It’s not too late.

Margaret McCartney is a GP partner, academic, broadcaster and writer

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on Twitter