Rachel Reeves will push to tap into the retirement savings of up to 6 million middle-class workers in plans Treasury officials presented ahead of her first budget.

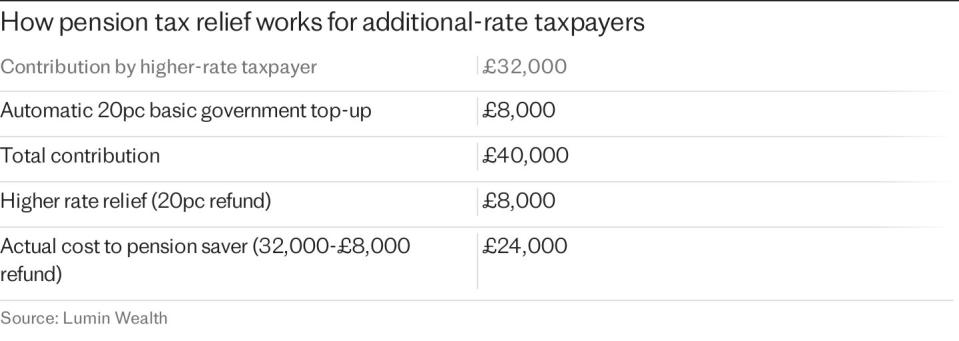

The Chancellor is expected to consider a proposal to cut pension tax to a flat rate of 30% – meaning higher rate payers would effectively pay 10% tax on their pension contributions for the first time.

The plan would affect up to six million higher-rate and additional taxpayers, costing the wealthiest savers around £2,600.

Ms Reeves had spoken in favour of restricting pension exemptions, but has since distanced herself from the proposals, insisting she has “no plans” to change the current system.

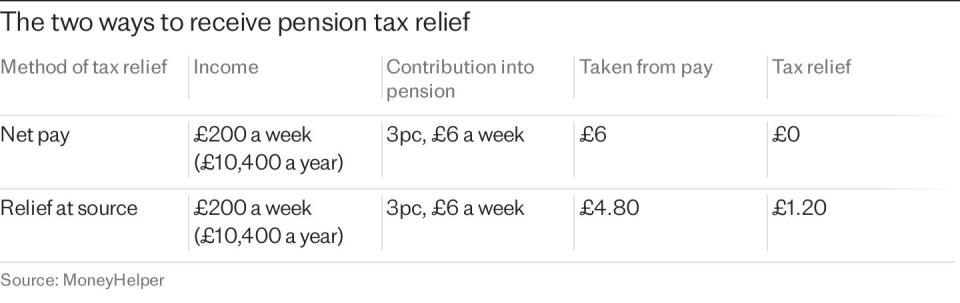

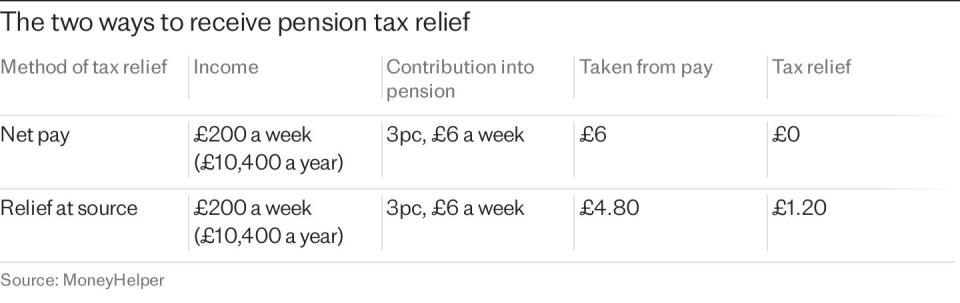

Pension contributions are tax deductible.This means that basic rate payers get a 20% relief on their payments to cancel out the income tax that would otherwise be due. Higher rate payers – those earning more than £50,270 – get a 40% relief, and most additional rate payers earning more than £125,140 get a 45% relief.

These rules cost the Treasury more than £50 billion a year through income tax relief, corporation tax relief, zero tax on growth in pensions, and the fact that employers do not have to pay National Insurance on pension contributions.

The Treasury has long wanted to tax retirement savings, and has drawn up a detailed plan to that end, which has been presented to successive chancellors since the coalition government came to power in 2010.

Proposals on the table include flat rates of 20% and 30%. Sources say the 30% rate would be more politically palatable because it could be given as a gift to millions of basic taxpayers, effectively increasing their pensions.

However, this would leave higher and additional taxpayers facing an effective fee of 10% or 15%.

Any change would spark anger in the pensions industry and lead to fears that many savers would stop paying in. It would also mean highest income earners You may end up being taxed twice on the same income, because withdrawals after retirement are also subject to income tax.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies said a flat 30% tax would be equivalent to a tax increase of £2.7bn. The policy would save the bottom 80% of earners around £230 a year, while the top earners would see an average tax increase of just under £2,600 a year.

The investment finance institution said reducing the income tax relief to the basic rate would represent a tax increase of £15.1 billion – roughly the same as a 2p increase in the basic rate of income tax.

The think tank said the “substantial increase” in tax would be borne almost exclusively by the top 20% of earners, with the top 10% facing an average hit of £4,300. The bottom 80%, who largely receive basic income tax relief from pension contributions, would see almost no change, the IFS said.

Sources familiar with the plans said moving to a flat 30% upfront rate could help “level out” the savings landscape with more generous support for the majority of workers who would benefit by hundreds of pounds each year.

In 2018, when Ms Reeves was chair of the Business Select Committee, she wrote a 66-page document outlining a series of tax reforms, including limiting tax breaks on pensions. “Forty per cent of UK wealth is held in private pension funds,” she said. “To combat this inequality, tax breaks on higher-rate pensions could be restricted.”

Two years ago, in 2016, it proposed setting the exemption at a flat rate of 33%. The Federal Statistical Institute said a rate of 32% would be nearly revenue-neutral, although freezing the personal allowance is expected to push millions of people into higher tax brackets in the coming years.

Experts said a 30% tax rate would force the Treasury to restrict Salary sacrifice pension planswhich currently provides a tax-efficient way for employers and employees to pay workplace pensions.

The Treasury has also carried out detailed work on the proposal, which could raise up to £3bn a year, and has analysed the restriction on exemptions from National Insurance contributions for employees and employers.

However, Sir Steve Webb, a former pensions minister and partner at pensions consultancy LCP, said this would discourage employers from “doing the right thing by penalising employers who contribute generously to workplace pensions”.

Research by the London School of Economics also showed that the generosity of employer contributions to workplace pension plans was the biggest incentive for people to save, increasing the chance of someone saving into a pension by 71%.

Sir Steve added that extending the restrictions to defined benefit schemes – which offer a guaranteed retirement income based on career earnings – would be very complex.

This is because most contributions to these schemes are made by the employer. For example, restricting the exemption to the basic rate is equivalent to having a taxable benefit go to taxpayers at higher rates. This could result in a large tax charge or a reduction in pensions in the event of an immediate tax.

Sir Steve said: “Giving everyone the same rate of tax relief on their pension contributions may seem fair, but it would be extremely complex to implement for millions of workers in traditional salary-linked pension schemes.

“The bulk of contributions to such schemes come from employers and are paid without any tax deduction. If high earners lose the tax relief at higher rates, they could face additional tax not only on their personal contributions but also on contributions made directly to the scheme by their employer. This bill could run into thousands of pounds a year in some cases.”

“We have identified the need for economic stability and have begun to repair the foundations so that we can grow our economy and keep taxes, inflation and mortgage rates as low as possible,” a Treasury spokesperson said.